Most photos © John or Ondine Kuraoka

Back to Cabo San Lucas and La Paz

23 December - Thursday was Mazatlan! We were at the buffet at 6:30, watching the haze

breaking and the early sun warming the rocky islands off Mazatlan. Perched atop

the highest, Isla Crestón, is what is claimed to be the world’s highest

working lighthouse, its light over 500 feet above sea level. The workers live

there 7 days on and 7 off; they have to carry all their food and supplies up by

hand. It’s a 45-minute walk from the beach to the lighthouse at the

peak. Here a tug chivvies us into position. The churning water you see is coming

from the Spirit’s azipods, which can rotate 360 degrees to provide thrust in any

direction.

We had a shore excursion scheduled: “Colonial Villages of the Sierra Madre.”

We were to be on the dock by 8:30, with a departure time of 9:30. Since everyone

on our bus arrived on-time, we actually departed 15 minutes early!

Our tour guide was Maria – she’d been a tour guide for 30 years. Her regular job was working in the DA’s office; before that she’d been a nurse. She’d married a Canuck and lived in Canada for many years, but after he died she moved back to her hometown of Mazatlan, where her family was.

Some hearty Americans at the front of the bus were noisily trying to persuade her to extend the tour to include the cathedral in Mazatlan. “The ship won’t leave without us,” they pleaded, “because this tour was booked through Carnival.” “But I’ll get fired,” she said. Still, they persisted.

Mazatlan is in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. Mazatl means “deer,” and Mazatlan means “land of the deer.” We’d be traveling by bus 30 miles into the mountains, following the Camino Real into 450-year-old villages. We hadn’t gone far when the landscape turned from coastal chaparral to tropical verdure. The mountains and foothills have deeply carved riparian wilds: Sinaloa means “land of 11 rivers.”

Mazatlan was founded as a colony in 1531. Conquistadores wiped out the aboriginal population and the void was quickly filled by immigrants. There were the Spanish, of course. Chinese laborers who worked on the railroads in the U.S. ended up settling in Mazatlan. There are French left over from Napoleon III’s invasion. Germans came and founded breweries – Cerveza Pacifico is one such. The local Amish and Mennonite communities are known for making cheese – “chihuahua,” which is a soft cheese similar to mozzarella. There’s even a significant Jewish influence – they helped fund the building of the cathedral with the result that Mazatlan’s Cathedral Basílica de la Immaculada Concepción is the world’s only Roman Catholic church with the Star of David displayed in each of its 28 stained-glass windows.

Our first stop was to watch adobe bricks being made by hand. It was a small,

family-run brickyard with a mud pit tucked into one corner and bricks in various

stages of development in neat sections. The mud and binder – rice and coffee

hulls as well as straw – are mixed by foot. They can’t dig too deep for the mud

– the site is on an old cemetery, something they learned when they dug up a

grave! They scoop out a barrowful of mud and slop an armload into a wooden frame

that makes four bricks. They smooth the mud by hand, and when they pull the

frame off seconds later, the mud is stiff enough to stay in place. Each family

member can make 500-1,500 bricks per day.

The bricks dry in the sun for a day or so before being stacked for further

drying. Then they use 12,000 raw bricks to build a tunnel-shaped kiln pointed

into the wind with hardwood stacked on the inside. The whole structure is

covered in skins and the wood is set alight. The fire burns for 7-10 days. The

bricks turn red when they’re fully fired.

There are factories down the road with machines churning out adobe bricks by the shipload. So small, family-run brickmakers are a dying business – but this one successfully shifted its focus from construction materials to tourism and entertainment. The children – out of school for the holidays – sold bracelets and collected tips. The adults solemnly continued their labor, conscious of photo opportunities but still working steadily. It was a little odd to walk off a bus into a family’s life and livelihood, peer at it as a curiosity, then clamber back aboard the bus to vanish, another bus disgorging tourists right behind. John pondered what it would be like to have Mexican tourists watching him write in his office. “This is an actual working writer,” their tour guide would say. “Mind the stacks of papers.”

From there we went to Malpica, “the land of the snakes.” It was established

in 1565 and burned by the French army in 1864. Its current population is about

350. There we walked down colonial streets, cobbled with stones and lined with

buildings hundreds of years old. The attraction in Malpica was Jorge, a tilemaker,

who made cement tiles with bright sworls of

color.

First the paint is spattered into the mold, followed by dollops of colored

cement. Then the mixture is swirled with a stick to create the design – one of

our tour group got to do the swirling! Atop that came layers of Portland cement

and white concrete. The tile is then pressed in a big steel press. The finished

tile is carefully pried out of the mold, and then air-cured for 15 hours.

We bought two tiles and Roy bought two tiles. We wondered again, though, whether Jorge’s real business was making tiles or putting on a tilemaking show for the tourists. Afterwards, we stopped at a bakery and bought some wonderful Mexican pastries to eat on the bus. Just as interesting as the traditional arts and crafts, is the fact that the small elementary school in Malpica is connected to its teachers via satellite – it’s all distance learning in that little town!

We stopped again at a place that made brightly colored pottery. All of us received a complimentary can of soda or bottle of water, and we meandered through the tables laden with silver, carved ironwood, beads, and pottery. Maria negotiated a special price on behalf of the group - $5 and $10 for carved wood, down from $10 and $15. Ondine bought some things to give the boys for Christmas.

Our next stop was Concordia, where Maria said Treasure of the Sierra Madre

was filmed. We walked a short distance to San Sebastian Church. Started in

the early 1600s and completed in 1706, San Sebastian is the oldest church in

Sinaloa. It’s a lovely example of Mexican Baroque. The arch partway up the nave

was used to separate the classes, Spanish from the “ethnics.” Like the other

churches, it’s a working community center – we had only a few minutes to look

around as a wedding was scheduled!

There’s an American Civil War connection: in 1864 the French invaded Mexico and set fire to many towns, including Concordia. It took a telegram from US President Abraham Lincoln to Napoleon III to get them to stop.

We continued our drive up into the mountains, through Chupadero, a small village with a tiny, perfectly whitewashed church that holds about 20 faithful. Along the way we passed several small farms carved out of the lush growth. The campasinos clear the brush with machetes and set fire to the cut greenery. The ash creates fertilizer in which they plant their corn. This “slash and burn” technique is an old way to farm.

Copala was our lunch stop. Copal means “sacred tree” in the aboriginal

language, and refers to an indigenous tree used for incense. Unfortunately

Copala also translates as “lake of gold” in Spanish, and the conquistadores

were looking for the “Seven Golden Cities.” The village of Copala was officially

founded in 1565. Gold was in fact discovered, along with silver. Copala sits

2,000 feet high, with a population of 600.

San Jose Church in Copala features a carved stone conquistador directly over

the entrance – he is rumored to spit on demons. There are three steps,

representing the holy trinity, and a low main door so “even kings have to bow

down.” It had a very colorful altar and a nativity scene at the entrance. A boy

in front of the church was selling little carved scraps of bark; Ondine bought

10 as omiyage.

From the church, we walked through the streets to our lunch stop. In that

first photo, the Butter referred to has nothing to do with the milk product.

Charles Butter was an early mine owner in Copala.

We had lunch at “Daniel’s Restaurant,” a sprawling concern much too large for

a town of 600. Its patio could probably seat half the town! Its founder was an

American expat from Huntington Beach. Lunch was chips and salsa, a chicken

enchilada, chicken tamale, and beef taco, with beans, rice, a scoop of salad,

dessert, and a drink. The meal was very good and unexpectedly light, with herbal

flavors instead of the usual hot/salty flavors associated with American Mexican

food. The salad was like coleslaw, with thinly sliced cabbage, lettuce, and

onion – perhaps with some local mango. It was slightly sweet and very

refreshing. The dessert was the “famous” banana coconut cream pie, which

Daniel’s restaurant claims to have invented. It too was excellent.

From Copala it was a 90-minute bus ride back into Mazatlan. While Leo, Roy,

and Ondine napped, John shot some of the pictures rolling by outside the bus

window, including one of the many rivers and random street scenes.

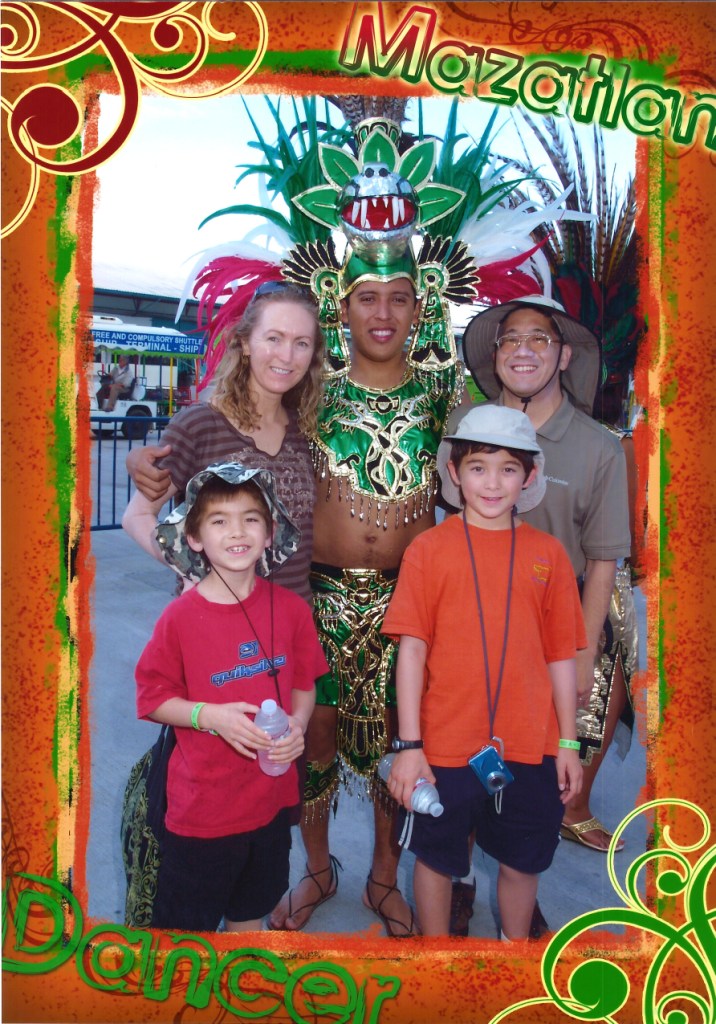

We got back to the dock – a working industrial dock – and took a “free and

mandatory shuttle” back to the ship. We spotted the crew doing some touch-up

painting! We hung out in the cabin, making door decorations. Then, we wandered

up to the buffet for dinner with Barbara and Bill. When we returned there was

another towel creature: an elephant! You can see how the ship sidles sideways

from the dock, as well as the light from the lighthouse!

After putting the boys to bed we sat out on the balcony eating plain yogurt and fresh pizza. Yum! Even with the wind and the choppy seas, it was positively balmy on our balcony. We heard a report from Barbara and Bill, who’d seen a news report – San Diego had been having “torrential rains” that flooded Qualcomm Stadium! But in Mexico, it was warm and clear all week!

Onward to Our Final Fun Days at Sea

Back to the Kuraoka Family main page